The Role of The United States in Nation-Building

December 15, 2021

“Nation-building” is when international influences challenge the current regime in an effort to change political objectives. For a foreign affair to be considered “Nation-building,” it must prompt military intervention. Nation-building also entails choosing people from one nation to serve in another nation’s government. For example, the United States government would select American officials and citizens to serve in a foreign government. For many Americans, the term “nation-building” provokes thoughts of Afghanistan. The United States invaded Afghanistan in 2003, with the hope of ending a terrorist regime and providing stability. Even though America desired to build a functional democracy, a product of their efforts was governmental corruption. Some government officials, diplomats, and military leaders argued that implementing a democracy and capitalist economy within Afghanistan, a nation of long-lasting tribal influences, was unfitting. Though it may appear this way, rebuilding Afghanistan benefited the nation’s youth. Death among young children has shown a significant decrease and the amount of children attending schools has grown tremendously. As a result of economic change, Afghanistan’s economy is five times larger than it was in 2001.

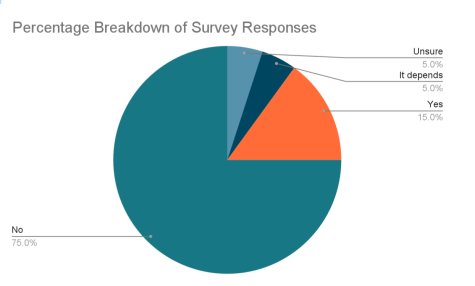

So, does the United States have the authority to establish democracies in other countries? We asked the Berkshire community this same question. Here is what they believed:

12th Grade Student:

“No. The United States has a reprehensible history when it comes to the concept of ‘nation-building’ or ‘spreading democracy.’ The frequency that the United States assassinates and overthrows democratically elected officials in other countries in favor of violent militaristic regimes to further political and economic interests is far too high. The results of these “democracy-spreading” missions are nothing short of neocolonial and imperialist.”

Faculty Member:

“The word establish comes from the Latin term stabilire which means to “make stable”. I believe that countries like the US have a duty to help countries who seek stability through democracy to establish a democracy.”

12th Grade Student:

“Yes, my country South Korea could have been North Korea without the United States. If it happened, I would be stuck under the communist system and pray for Kim Jong-Eun 24/7. I am aware in some cases, there are adverse outcomes. But still, I think it is necessary to have powerful countries do what they believe is the right way to achieve world peace.”

9th Grade Student:

“Most of the time no, but in situations where the government in place has a very high probability to harm the US or our allies, yes.”

10th Grade Student:

“No we do not. The United States is just that, a country with many states united under one government, we don’t control others. We may help other countries when they ask for it, but we should not go dictating and controlling other countries. Instead of using our energy on controlling other countries, we need to focus back on the issues here in the US, I could name a few dozen.”

9th Grade Student:

“It’s not our place to have opinions of other countries. I feel as if we have to get our country under control before we go and tell other countries how to govern. If a country reached out to us then sure, lets help but other than that. We should not be including ourselves in other countries’ politics.”

Faculty Member:

“No – they might be able to help a country that is already in the process of changing to a democracy, but they should not just jump in and tell another country what to do.”

Picture yourself living in the French countryside. It is the year 1860, you’re twelve years old, and you have never left your small village. In your twelve years of age, you have never learned French. You have never expressed interest or respect, frustration or sentiment toward your own government; it seems as distant as your own national language. Forty years pass, you are fifty two years old, and it is the year 1900. Your children have just wandered through the door, speaking French so fluently that you are left awestruck and clueless. Their mandatory state-run schooling has taught them this language. To do so, the school has banned your language within school grounds. Nostalgia brings you to a time where your upbringing was not muffled by law. You glance up, frowning, silenced by a homogenized society, but your children just smile.

Now picture yourself in the United States, it is the year 2012, and you are eighteen years old. You have lived in Ohio your entire life, always feeling the presence of abandoned factories, skeletons of the rustbelt. You are on track to be the valedictorian, but you question graduating high school. Your mother comes home from work, carrying in meals from the food pantry; she leaves in a hustle for the night shift. The TV murmurs about the 60 billion dollars the U.S. has spent in rebuilding Iraq. Next door, the neighbors house is empty. The family has left for the cemetery. They are mourning the loss of their son, brave and young, who gave his life to support the United States in the Iraq War. The war has reinforced and augmented poverty and businesses flee. Your town is suddenly hollow, quickly emptied, yet deprivation dwindles.

Take this fictional narrative and think to yourself: does humanizing these stories change your opinion?